| Issue |

4open

Volume 2, 2019

Difference & Differential Equations and Applications

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | 2 | |

| Number of page(s) | 11 | |

| Section | Mathematics - Applied Mathematics | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/fopen/2018010 | |

| Published online | 04 March 2019 | |

Research Article

More on algebraic properties of the discrete Fourier transform raising and lowering operators★

1

Centro de Investigación en Ciencias, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos,

Cuernavaca,

62250 Morelos, México

2

Instituto de Matemáticas, Unidad Cuernavaca, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México,

Cuernavaca,

62210 Morelos, México

3

Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí,

San Luis Potosí,

78290 SLP, México

* Corresponding author: natig_atakishiyev@hotmail.com

Received:

20

December

2018

Accepted:

27

December

2018

In the present work, we discuss some additional findings concerning algebraic properties of the N-dimensional discrete Fourier transform (DFT) raising and lowering difference operators, recently introduced in [Atakishiyeva MK, Atakishiyev NM (2015), J Phys: Conf Ser 597, 012012; Atakishiyeva MK, Atakishiyev NM (2016), Adv Dyn Syst Appl 11, 81–92]. In particular, we argue that the most authentic symmetrical form of discretization of the integral Fourier transform may be constructed as the discrete Fourier transforms based on the odd points N only, while in the discrete Fourier transforms on the even points N this symmetry is spontaneously broken. This heretofore undetected distinction between odd and even dimensions is shown to be intimately related with the newly revealed algebraic properties of the above-mentioned DFT raising and lowering difference operators and, of course, is very consistent with the well-known formula for the multiplicities of the eigenvalues, associated with the N-dimensional DFT. In addition, we propose a general approach to deriving the eigenvectors of the discrete number operators N(N), that avoids the above-mentioned pitfalls in the structure of each even-dimensional case N = 2L.

Key words: Algebraic properties / Discrete Fourier transform (DFT) / Difference equations

© M.K. Atakishiyeva et al., Published by EDP Sciences 2019

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

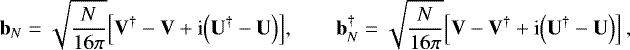

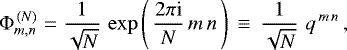

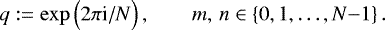

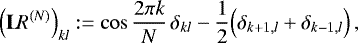

In the present work, we discuss some additional findings concerning algebraic properties of the discrete (finite) Fourier transform (DFT) raising and lowering difference operators, recently introduced in [1, 2]. Perhaps, it is worthwhile to recall first that the DFT based on points N is represented by an N × N unitary symmetric matrix  with entries

with entries

(1)

(1)

This matrix Φ(N) was introducedby Sylvester [3] in 1867 and frequently referred to as Schur’s matrix.

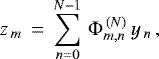

Given a complex valued vector y⃗ with components  , one can compute another vector z⃗ with components

, one can compute another vector z⃗ with components

(2)

(2)

referred to as the DFT of the vector y⃗. Those vectors f⃗( k), which are solutions of the standard equations

(3)

(3)

then represent eigenvectors of the DFT operator Φ(N), associated with the eigenvalues λk. Since the fourth power of Φ(N) is the unit operator, the only four distinct eigenvalues among λk’s are ± 1 and ± i.

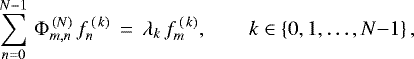

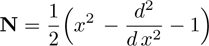

An important aspect to observe at this point is that the same type of degeneracy of the eigenvalues is characteristic of the continuous counterpart of the DFT, the Fourier integral transform (FIT) that is also a unitary operator of order 4 with the same eigenvalues ± 1 , ± i. Note also that it is customary to reduce the problem of deriving the eigenfunctions of FIT to that of finding a differential operator of the lowest order with distinct eigenvalues, that commutes with the FIT operator and therefore has the same set of eigenfunctions as the FIT operator. Such differential operator was found to be a second-order differential number operator

(4)

(4)

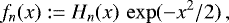

which has distinct eigenvalues λn := n, n = 0, 1, 2, … , associated with the eigenfunctions

(5)

(5)

where Hn(x) are the Hermite polynomials [4]. Thus in this way not only the eigenfunctions of the FIT are found, but their degeneracies are lifted by enumerating those eigenfunctions with the aid of the distinct eigenvalues λn = n of the number operator N. Note that the functions fn(x) are usually referred to as Hermite functions in the mathematical literature and, properly normalized, they represent the wave functions of the linear harmonic oscillator in non-relativistic quantum mechanics [5].

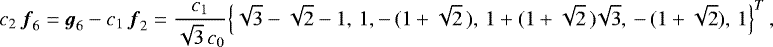

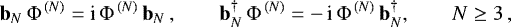

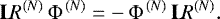

So, an attempt has been made in [1] to find, in complete analogy with the case of IFT operator, such an operator with distinct eigenvalues that commutes with the DFT operator Φ(N) . Since from the outset it was evident that this required operator cannot be any differential operator of a finite order, it was proposed to construct first two difference lowering and raising operators b N and  with the aid of the standard intertwining relations

with the aid of the standard intertwining relations

(6)

(6)

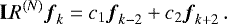

with the DFT operator Φ(N). Then it is straightforward to verify, by using definition (6), that a discrete number operator, defined as a difference operator of the form

(7)

(7)

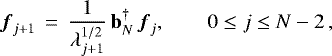

does commute with the DFT operator Φ(N). Therefore, it was conjectured in [1] that the eigenvalues of the discrete number operator  , based on an arbitrary number of points N, are represented by distinct non-negative numbers and the corresponding eigenvectors f⃗ k , 0 ≤ k ≤ N − 1, can be successively defined, with the aid of the raising operator

, based on an arbitrary number of points N, are represented by distinct non-negative numbers and the corresponding eigenvectors f⃗ k , 0 ≤ k ≤ N − 1, can be successively defined, with the aid of the raising operator  , as

, as

(8)

(8)

starting with the lowest eigenvector f⃗0, which is found as a solution of the difference equation

(9)

(9)

In order to test the consistency of this approach to finding eigenfunctions and eigenvalues of the DFT operator Φ(N) , the particular case of the 5-dimensional DFT was studied in detail in [6]. It was confirmed that the eigenvalues of the discrete number operator  are represented by distinct non-negative numbers and the corresponding eigenvectors f⃗ k , 0 ≤ k ≤ 4, can be successively defined with the aid of the raising operator

are represented by distinct non-negative numbers and the corresponding eigenvectors f⃗ k , 0 ≤ k ≤ 4, can be successively defined with the aid of the raising operator  and the lowest eigenvector f⃗0, which is found as a solution of the difference equation b5 f⃗0 = 0.

and the lowest eigenvector f⃗0, which is found as a solution of the difference equation b5 f⃗0 = 0.

The purpose of this presentation is to discuss some novel findings concerning algebraic properties of the N-dimensional DFT lowering and raising difference operators bN and  . In particular, we evaluate in the next Section 2 the rank of lowering difference operator b N (which is the same as the rank of the raising operator

. In particular, we evaluate in the next Section 2 the rank of lowering difference operator b N (which is the same as the rank of the raising operator  ) for an arbitrary dimension N. It turns out the rank of the bN is equal to N − 1 for odd dimensions N, whereas it is equal to N − 2 for even dimensions N. This proves that the discrete number operator

) for an arbitrary dimension N. It turns out the rank of the bN is equal to N − 1 for odd dimensions N, whereas it is equal to N − 2 for even dimensions N. This proves that the discrete number operator  has a distinct spectrum only for odd dimensions N; the corresponding eigenvectors in all these cases can be successively constructed with the aid of (8) and (9). As for even dimensions N, this means that in those cases the discrete number operator

has a distinct spectrum only for odd dimensions N; the corresponding eigenvectors in all these cases can be successively constructed with the aid of (8) and (9). As for even dimensions N, this means that in those cases the discrete number operator  has two repeated zero eigenvalues and one should therefore look for a non-standard way of finding the eigenvectors of the

has two repeated zero eigenvalues and one should therefore look for a non-standard way of finding the eigenvectors of the  and relevantly ordering them. In Section 3, it is shown that this heretofore undetected distinction between DFTs based on odd and even points N is very consistentwith the well-known formula [7, 8] for the multiplicities of the eigenvalues, associated with the N-dimensional DFT operator Φ(N). Finally, in Section 4, we put forward a general algorithm for constructing the eigenvectors of the discrete number operators

and relevantly ordering them. In Section 3, it is shown that this heretofore undetected distinction between DFTs based on odd and even points N is very consistentwith the well-known formula [7, 8] for the multiplicities of the eigenvalues, associated with the N-dimensional DFT operator Φ(N). Finally, in Section 4, we put forward a general algorithm for constructing the eigenvectors of the discrete number operators  , that avoids the above-mentioned pitfalls in the structure of each even-dimensional case N = 2L.

, that avoids the above-mentioned pitfalls in the structure of each even-dimensional case N = 2L.

N-dimensional raising and lowering operators

Algebraic properties of the N-dimensional DFT lowering bN and raising  difference operators were broached in [2] by the first two authors of this presentation. The development is continued here. In particular, in this section we extend those results by evaluating the rank of the operators b N and

difference operators were broached in [2] by the first two authors of this presentation. The development is continued here. In particular, in this section we extend those results by evaluating the rank of the operators b N and  for an arbitrary dimension N and demonstrating that the characteristic equations for those operators have a particular ‘cyclic’ form.

for an arbitrary dimension N and demonstrating that the characteristic equations for those operators have a particular ‘cyclic’ form.

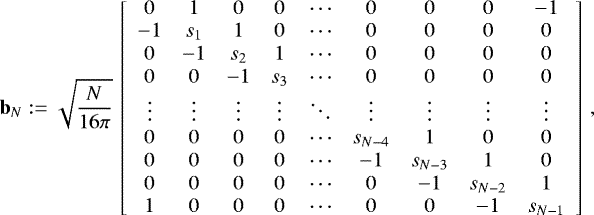

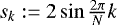

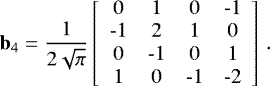

The N-dimensional lowering difference operator is represented by the N × N matrix

(10)

(10)

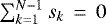

where we introduced for brevity  , 0 ≤ k ≤ N − 1, and N is an arbitrary positive integer, N ≥ 3.

, 0 ≤ k ≤ N − 1, and N is an arbitrary positive integer, N ≥ 3.

Notice that the matrix in (10) is traceless, because one checks easily that  . Also, since sN−k = − sk by definition of the parameterssk, the diagonal elements of the matrix in (10) are of the form

. Also, since sN−k = − sk by definition of the parameterssk, the diagonal elements of the matrix in (10) are of the form

(11)

(11)

for even andodd dimensions N, respectively. This means that the operator bN depends only on the L independent parameters {s1, s2, …, sL} if N = 2L + 1 and on the L − 1 parameters {s1 , s2 , … , sL−1} if N = 2L.

The matrix bN is noninvertible (singular) and its rank is different for the even and odd dimensions N. This can be shown in the following way.

We recall first that the space spanned by the rows (columns) of a matrix A is called the row (column) space of A; its dimension is called the row (column) rank. The rank of a matrix equals the row (column) rank [9]. There are simple procedures available for finding bases for the row and column spaces of a matrix.

To find a basis of the row (column) space of a matrix A, use elementary row (column) operations to put A in reduced row (column) echelon form. Discard any zero rows (columns); then the remaining rows (columns) will form a basis of the row (column) space of A (see, for example, pages 41, 44, 49 and 127 in [10]).

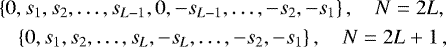

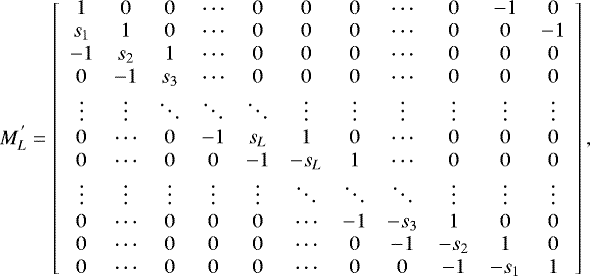

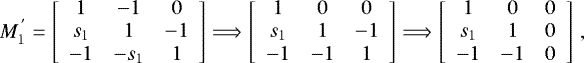

So, let us begin with examining the matrix  for odd N = 2L + 1, L ≥ 1, where the matrix ML is

for odd N = 2L + 1, L ≥ 1, where the matrix ML is

(12)

(12)

By elementary column operations one may cast the matrix ML into the form

(13)

(13)

which is almost in the column echelon form, except for the two elements equal to − 1 on the upper right corner of this matrix. But it is not hard to eliminate them by further elementary column operations over the last two columns, and bring  into complete column echelon form. Indeed, let us add to the penultimate column in (13) its first column plus the last one, multiplied by the parameter s1, to get

into complete column echelon form. Indeed, let us add to the penultimate column in (13) its first column plus the last one, multiplied by the parameter s1, to get

(14)

(14)

So, the next step is to add to the last column in (14) the second column plus the penultimate one, multiplied by the parameter s2; this results in

(15)

(15)

Let us emphasize that this form  of the initial matrix ML contains the principal minor

of the initial matrix ML contains the principal minor  , of order N − 2 ≡ 2(L − 1) + 1, which results from the deletion of the first two rows and columns in (15), as indicated there by dashed line. This minor has a structure similar to the matrix

, of order N − 2 ≡ 2(L − 1) + 1, which results from the deletion of the first two rows and columns in (15), as indicated there by dashed line. This minor has a structure similar to the matrix  in (13). One therefore may employ the same type of elementary column operations as above in order to move those two elements equal to − 1 in the last twocolumns in (15) another two rows down. Repeating those steps L − 1 times, one finally arrives at the form, which contains a principal minor of order 3 on its lower right corner; this minor has the same structure as

in (13). One therefore may employ the same type of elementary column operations as above in order to move those two elements equal to − 1 in the last twocolumns in (15) another two rows down. Repeating those steps L − 1 times, one finally arrives at the form, which contains a principal minor of order 3 on its lower right corner; this minor has the same structure as  . It is plain that in the latter case

. It is plain that in the latter case

(16)

(16)

where we added the first column plus the third column, multiplied by s1 , to the second column at the first step, and the second column to the third one at the second step. This means that the matrix ML is finally reduced to the complete column echelon form of a lower triangular matrix, which has nonzero first N − 1 diagonal elements and only one zero element on its main diagonal. Hence det ML = 0, rank ML = N − 1 and the null space of the matrix ML is one-dimensional. One therefore sees that the lowest eigenvector f⃗0 of the discrete number operator  is uniquely determined (up to normalization by a proper constant) by the equation b N f⃗ 0 = 0 and all other N − 1 eigenvectors f⃗ j , 1 ≤ j ≤ N − 1 of the operator

is uniquely determined (up to normalization by a proper constant) by the equation b N f⃗ 0 = 0 and all other N − 1 eigenvectors f⃗ j , 1 ≤ j ≤ N − 1 of the operator  , successively defined by (8), are linearly independent.

, successively defined by (8), are linearly independent.

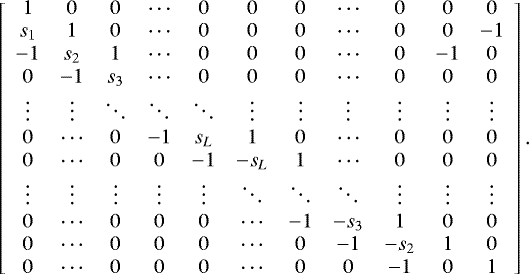

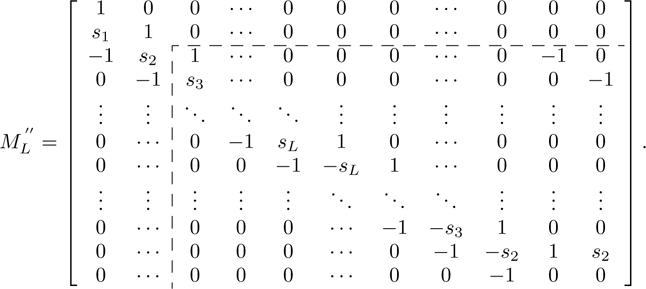

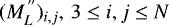

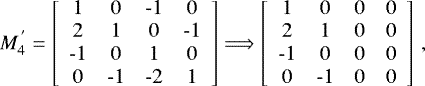

Turning now to the case of the matrix bN with even N = 2L, L ≥ 2, it should be noted that the corresponding matrix in (10) for even N = 2L has almost the same structure as ML in the odd case, except that only diagonal elements of those two matrices are different: as indicated in (11), there are two zero diagonal elements in the even case N = 2L and only one zero element in the odd caseN = 2L + 1. Therefore, onemay likewise employ the same inductive procedure in L as in the odd case N = 2L + 1 in order to move downwards those two elements equal to − 1 in the last two columns of the matrix  , finally arriving at the form with aprincipal minor of order 4 on its lower right corner. This principal minor has the same structure as

, finally arriving at the form with aprincipal minor of order 4 on its lower right corner. This principal minor has the same structure as  ,

,

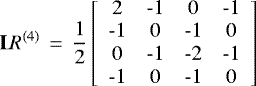

(17)

(17)

which is readily reduced to the echelon form, indicated in the above. One therefore checks easily that all even case matrices can be transformed, by elementary column operations, into the complete echelon form with two zero columns at the end. Thus in the even N = 2L case det b N = 0, rank b N = N − 2 and the null space of the matrix bN is two-dimensional. This means that in the even case there are two linearly independent solutions of the difference equation b N f⃗ 0 = 0 for defining the lowest eigenvector of the discrete number operator  .

.

Let us draw attention now to the remarkable ‘cyclic’ properties of the lowering and raising difference operators b N and  , which can be formulated in the following way. Recall first that the equation which is solved to find eigenvalues of N × N matrix M is usually interpreted as the equation for finding roots of the characteristic polynomial

, which can be formulated in the following way. Recall first that the equation which is solved to find eigenvalues of N × N matrix M is usually interpreted as the equation for finding roots of the characteristic polynomial

(18)

(18)

where I is the N × N identity matrix and the coefficient ck is  times the sum of the determinants of all of the principal k × k minors of M (note that by this definition c1 = − trace(M) and

times the sum of the determinants of all of the principal k × k minors of M (note that by this definition c1 = − trace(M) and  ). The Cayley–Hamilton theorem then states that an N × N matrix M is annihilated by its characteristic polynomial (18), that is,

). The Cayley–Hamilton theorem then states that an N × N matrix M is annihilated by its characteristic polynomial (18), that is,

(19)

(19)

It is plain that for a singular traceless matrix M the coefficients c1 and cN vanish. It turns out that for the particular traceless matrices of the form b N and  there are many more vanishing coefficients in the identity (19). The point is that from the defining intertwining relations (6) for the lowering and raising difference operators b N and

there are many more vanishing coefficients in the identity (19). The point is that from the defining intertwining relations (6) for the lowering and raising difference operators b N and  it follows at once that

it follows at once that

(20)

(20)

This means that if, for instance, bNf⃗ = λ f⃗ and λ≠ 0, then  , where the eigenvector

, where the eigenvector  of the operator bN is defined as

of the operator bN is defined as  . Hence, if the operator b N has nonzero eigenvalue λ, associated with the eigenvector f⃗, then it has another eigenvalue −iλ, associated with the eigenvector

. Hence, if the operator b N has nonzero eigenvalue λ, associated with the eigenvector f⃗, then it has another eigenvalue −iλ, associated with the eigenvector  , as well. Moreover, since the DFT operator Φ(N) is of order 4, each nonzero eigenvalue λ is actually accompanied by the 3 other eigenvalues ik λ , k = 1, 2, 3. Since the polynomial(z − λ)(z −iλ)(z + λ)(z + iλ) = z4 − λ4, one therefore concludes that in the characteristic equation (19) for the lowering operator b N , N ≥ 5, the only nonzero coefficients are c4, c8, …, c4k, where k := [N∕4] and the symbol [X] stands for the greatest integer in X. This characteristic equation can be thus written in the ‘cyclic’ form as

, as well. Moreover, since the DFT operator Φ(N) is of order 4, each nonzero eigenvalue λ is actually accompanied by the 3 other eigenvalues ik λ , k = 1, 2, 3. Since the polynomial(z − λ)(z −iλ)(z + λ)(z + iλ) = z4 − λ4, one therefore concludes that in the characteristic equation (19) for the lowering operator b N , N ≥ 5, the only nonzero coefficients are c4, c8, …, c4k, where k := [N∕4] and the symbol [X] stands for the greatest integer in X. This characteristic equation can be thus written in the ‘cyclic’ form as

(21)

(21)

where 0 ≤ l := N − 4k ≤ 3 and λ1 , λ2, …, λk are some constants.

To close this section, we recall here that the raising difference operator  is the matrix transpose of the lowering difference operator bN; hence the former operator has the same set of properties as the latter one: the vanishing determinant and trace, the same rank, distinct for even and odd dimensions N, and the same characteristic equation (21).

is the matrix transpose of the lowering difference operator bN; hence the former operator has the same set of properties as the latter one: the vanishing determinant and trace, the same rank, distinct for even and odd dimensions N, and the same characteristic equation (21).

Multiplicities

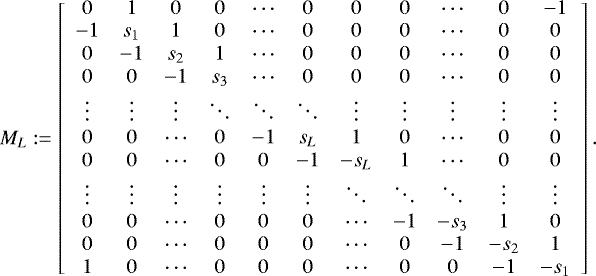

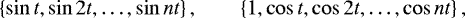

As a starting point in this section, let us take the two so-called Chebyshev sets

(22)

(22)

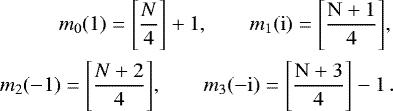

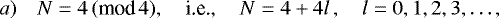

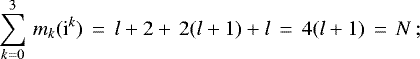

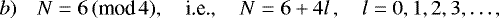

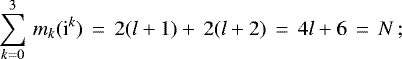

which are defined on intervals (0, π) and [0, π], respectively. These sets were employed in [7, 8] to give a simple proof of the explicit expressions for the multiplicities mk (ik ) of the eigenvalues ik, 0 ≤ k ≤ 3, for the N-dimensional DFT operator Φ(N) of the form:

(23)

(23)

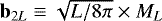

Note that the lowering bN and raising  difference operators, as well as their product, the discrete number operator

difference operators, as well as their product, the discrete number operator  , do depend on the set of parameters {s1, s2, …, sN−1}, which may be regarded as the particular case of the Chebyshev set of smooth functions taken at the distinct points tk := 2πk∕N, 1 ≤ k ≤ (N − 1). Thus, the fact that this particular set of parameters {s1, s2, …, sN−1} plays a key role in our study, is not accidental at all. But the real reason for mentioning here the formula (23) for multiplicities is the following.

, do depend on the set of parameters {s1, s2, …, sN−1}, which may be regarded as the particular case of the Chebyshev set of smooth functions taken at the distinct points tk := 2πk∕N, 1 ≤ k ≤ (N − 1). Thus, the fact that this particular set of parameters {s1, s2, …, sN−1} plays a key role in our study, is not accidental at all. But the real reason for mentioning here the formula (23) for multiplicities is the following.

The formula (23) had been known for a long time before the appearance of the above-mentioned papers [7 , 8 ]. Nevertheless, what seems to remain unnoticed is that this formula clearly points out the dissimilarity between ordering the even-dimensional eigenvectors and odd-dimensional eigenvectors of the DFT operator Φ(N) . This can be argued in the following way.

Imagine that one has a set of N marbles in 4 colors: m0(1) green, m1(i) blue, m2(−1) yellow, and m3(−i) red ones; the marbles of the same color are assumed for the moment to be identical. Also, there are boxes of various sizes with n + 1 compartments, which are consecutively labeled by 0, 1, 2, …, n. The question is how to select a box of minimal size in order to arrange in it, one by one, all the N marbles, taking into account that the green marbles may be placed only into compartments, marked as 0, 4, 8, … , blue marbles – into compartments, marked as 1, 5, 9, … , yellow marbles – into compartments, marked as 2, 6, 10, … , and red ones – into compartments 3, 7, 11, … .

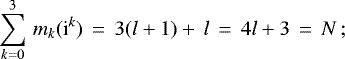

To solve this rather simple combinatorial problem, observe that all odd dimensions N ≥ 3 can be divided intotwo sets as:

in particular, for N = 3 (i.e., l = 0) this set can be schematically depicted as

in particular, for N = 5 (i.e., l = 0) this set can be schematically depicted as

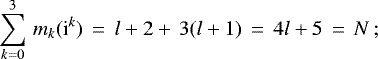

By the same token, all even dimensions N ≥ 4 can be divided into two sets of the form:

in particular, for N = 4 (i.e., l = 0) this set can be schematically depicted as

in particular, for N = 6 (i.e., l = 0) this set can be schematically depicted as

Inspection of Figures 1–4 indicates that for each odd number N of marbles it is sufficient to use a box, which contains only N compartments in it; whilst in the case of all even numbers N of marbles one needs to use boxes with N + 1 compartments in them. Thus simply by examining the well-known equation (23) for the multiplicities of the eigenvalues for the N-dimensional DFT operator Φ(N) one arrives at the same conclusions concerning essential differences between symmetry properties of the eigenvectors for the even- and odd-dimensional DFT operator, as we elaborated at the end of the previous section.

Eigenvectors for the even cases N=2L

It is evident now that for all even dimensions N = 2L there are multiple eigenvalues in the spectrum of the discrete number operator  and there is always a gap in the associated with them multiplicities (23) (see Figs. 3 and 4). Hence, it is not possible to employ the same conventional algorithm for finding the eigenvectors of the operator

and there is always a gap in the associated with them multiplicities (23) (see Figs. 3 and 4). Hence, it is not possible to employ the same conventional algorithm for finding the eigenvectors of the operator  as in the case of odd dimensions N = 2L + 1, when the all appropriate eigenvectors are successively constructed with the aid of the difference raising

as in the case of odd dimensions N = 2L + 1, when the all appropriate eigenvectors are successively constructed with the aid of the difference raising  and lowering bN operators via (8) and (9). However, it turns out that there is a more elaborate way of finding the eigenvectors for the

and lowering bN operators via (8) and (9). However, it turns out that there is a more elaborate way of finding the eigenvectors for the  , which enables one to surmount the above-mentioned obstacles in the structure of the each even-dimensional discrete number operator

, which enables one to surmount the above-mentioned obstacles in the structure of the each even-dimensional discrete number operator  and its spectrum.

and its spectrum.

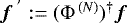

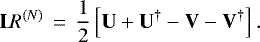

The key step in our approach towards finding the eigenvectors of the operator  is the use of certain properties of an additional lowering-raising operator LR(N) of the form

is the use of certain properties of an additional lowering-raising operator LR(N) of the form

(24)

(24)

where 0 ≤ k, l ≤ N − 1, δ−1,l = δN−1,l and δN,l = δ0,l. As detailed in Section 3 of [1], thus introduced operator LR(N) anticommutes with the DFT operator Φ(N), that is,

(25)

(25)

From (25) it follows at once that the action of the operator LR(N) on the eigenvector f⃗ k of the DFT operator Φ(N) , associated with the eigenvalue ik, 0 ≤ k ≤ 3, is a linear combination of the two eigenvectors f⃗k−2 and f⃗ k+2 of the DFT operator Φ(N), i.e.,

(26)

(26)

That is why this operator is regarded as a double step lowering–raising difference operator and denoted by the symbol LR(N) .

Remark 1.

The algebraic interpretation of the lowering and raising difference operators

b N and

is more transparent when they are expressed in terms of the complementary pair of the unitary operators

U and

V on

is more transparent when they are expressed in terms of the complementary pair of the unitary operators

U and

V on

as

as

where Uk,l := qkδk,l and V k,l := δk,l+1 (see [1, 2]). The self-adjoint difference operator LR(N) can be written in terms of these unitary operators U and V as

(28)

(28)

We are nowin a position to discuss an appropriate algorithm for finding the eigenvectors of the discrete number operator  . Recall first that all even dimensions N ≥ 4 under study in this section can be divided into two subsets of dimensions N = 4 (mod 4) and N = 6 (mod 4). Moreover, all hierarchies of the eigenvectors of the

. Recall first that all even dimensions N ≥ 4 under study in this section can be divided into two subsets of dimensions N = 4 (mod 4) and N = 6 (mod 4). Moreover, all hierarchies of the eigenvectors of the  within the first subset have the same structure as in the case of N = 4 (see Fig. 3), whereas all sets of the eigenvectors from the second subset exhibit the same structure as in the case of N = 6 (see Fig. 4).

within the first subset have the same structure as in the case of N = 4 (see Fig. 3), whereas all sets of the eigenvectors from the second subset exhibit the same structure as in the case of N = 6 (see Fig. 4).

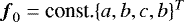

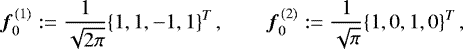

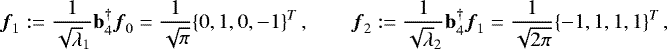

(a) Let us begin with examining the case of N = 4, when the lowering difference operator b4 is represented by the 4 × 4 matrix,

(29)

(29)

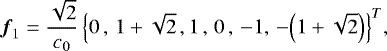

As in the odd case with N = 2L + 1, the lowest eigenvector  is found as a solution of the difference equation b4f⃗0 = 0. Unlike the odd case with N = 2L + 1, this equation has two linearly independent solutions of the form

is found as a solution of the difference equation b4f⃗0 = 0. Unlike the odd case with N = 2L + 1, this equation has two linearly independent solutions of the form

(30)

(30)

and both of these solutions are eigenvectors of the DFT operator Φ(4) , associated with the same eigenvalue i0 = 1. It is to be remarked that in this case one readily identifies that the second solution  actually represents the last eigenvector f⃗4 in the hierarchy of all eigenvectors of the discrete number operator

actually represents the last eigenvector f⃗4 in the hierarchy of all eigenvectors of the discrete number operator  (see Fig. 3), because it is annihilated also by the raising difference operator

(see Fig. 3), because it is annihilated also by the raising difference operator  , that is,

, that is,  . As for the first solution

. As for the first solution  , it may be usedto find the two remaining linearly independent eigenvectors of the discrete number operator

, it may be usedto find the two remaining linearly independent eigenvectors of the discrete number operator  as

as

(31)

(31)

where  and λ1 = λ2 = 2∕π. The 4 orthonormal vectors f⃗0, f⃗1, f⃗2 and f⃗ 4 thus form a complete set of the eigenvectors for the discrete number operator

and λ1 = λ2 = 2∕π. The 4 orthonormal vectors f⃗0, f⃗1, f⃗2 and f⃗ 4 thus form a complete set of the eigenvectors for the discrete number operator  , associated with the eigenvalues λ0 = 0, λ1 = λ2 = 2∕π, λ4 = 0, respectively.

, associated with the eigenvalues λ0 = 0, λ1 = λ2 = 2∕π, λ4 = 0, respectively.

It remains only to add that in this case with N = 4 there is no need to use the lowering-raising operator

(32)

(32)

in order to find the eigenvector f⃗4 next to the gap in the set of all eigenvectors f⃗k, 0 ≤ k ≤ 4, since from the very beginning this eigenvector surfaces as the second solution in (30) of the difference equation b 4 f⃗ 0 =0. However, as the consistency check of our approach to finding the eigenvectors of the discrete number operator  , one may verify that the operator LR(4) does express the vector f⃗4 in terms of the vector f⃗2, i.e., over the above-mentioned gap, as

, one may verify that the operator LR(4) does express the vector f⃗4 in terms of the vector f⃗2, i.e., over the above-mentioned gap, as

(33)

(33)

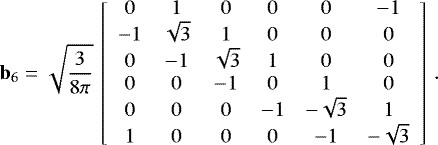

(b) In the case of N = 6 the lowering difference operator b6 is represented by the 6 × 6 matrix,

(34)

(34)

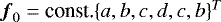

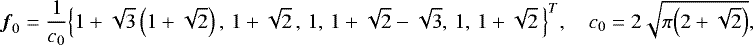

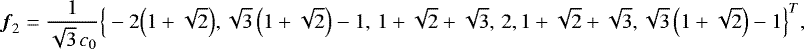

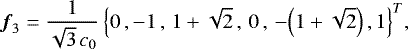

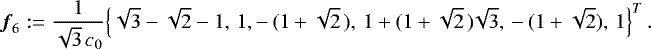

Similar to the odd case with N = 2L + 1, the lowest eigenvector  is found as a solution of the difference equation b6f⃗0 = 0. This equation has only one solution of the form

is found as a solution of the difference equation b6f⃗0 = 0. This equation has only one solution of the form

(35)

(35)

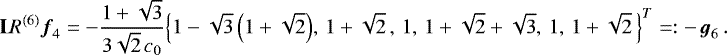

which represents at the same time the eigenvector of the DFT operator Φ(6) , associated with the eigenvalue i 0 = 1. Since the rank of the difference raising operator  is equal to 4, the next 4 linearly independent eigenvectors are then successively defined to be

is equal to 4, the next 4 linearly independent eigenvectors are then successively defined to be

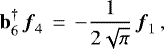

(36)

(36)

(37)

(37)

(38)

(38)

(39)

(39)

by using the conventional sequence of formulas (8). All these eigenvectors f⃗ k , 1 ≤ k ≤ 4, are associated with the same eigenvalues λk = 9∕4π of the discrete number operator  ; at the same time they are associated with the eigenvalues ik of the DFT operator Φ(6), respectively.

; at the same time they are associated with the eigenvalues ik of the DFT operator Φ(6), respectively.

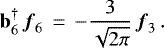

Observe that the subsequent action of the raising difference operator  on the eigenvector f⃗4 gives

on the eigenvector f⃗4 gives

(40)

(40)

which is consistent with the equation (23) for the multiplicities in the 6-dimensional case (see Fig. 4).

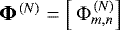

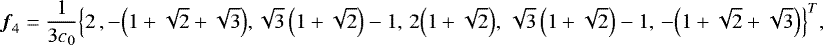

To find the last eigenvector f⃗6 of the discrete number operator  , let us evaluate first

, let us evaluate first

(41)

(41)

From (26) it follows that g⃗6 = c1f⃗2 + c2f⃗6 and to define the first coefficient c1 in this linear combination of the vectors f⃗2 and f⃗ 6 , one evaluates next that

(42)

(42)

from which it follows at once that c2 = c1 and

(44)

(44)

It is not hard to verify that thus defined vector f⃗ 6 is the eigenvector of the discrete number operator  , associated with the vanishing eigenvalue λ6 = 0; and of the DFT operator Φ(6), associated with the eigenvalue i2 = −1. Note that the gap in this particular case of N = 6, originated from the absence of the eigenvector labeled n = 5, is justified by the readily verified identity b6f⃗6 = 0. Also, the subsequent action of the raising difference operator

, associated with the vanishing eigenvalue λ6 = 0; and of the DFT operator Φ(6), associated with the eigenvalue i2 = −1. Note that the gap in this particular case of N = 6, originated from the absence of the eigenvector labeled n = 5, is justified by the readily verified identity b6f⃗6 = 0. Also, the subsequent action of the raising difference operator  on the eigenvector f⃗6 does not generate anything novel since

on the eigenvector f⃗6 does not generate anything novel since

(45)

(45)

The 6 orthonormal vectors f⃗k, 0 ≤ k ≤ 4 and f⃗ 6 , defined by equations (35)–(39) and (44), thus form a complete set of the eigenvectors for the discrete number operator  , associated with the eigenvalues λ0 = 0, λ1 = λ2 = λ3 = λ4 = 9∕4π, and λ6 = 0, respectively.

, associated with the eigenvalues λ0 = 0, λ1 = λ2 = λ3 = λ4 = 9∕4π, and λ6 = 0, respectively.

This concludes our use of the difference operator LR(N) to illustrate a systematic approach to deriving the eigenvectors of the discrete number operator  for even N′ s.

for even N′ s.

Concluding remarks

It is well known that from the outset the N-dimensional DFT operator Φ(N) was conceived as a discrete (finite) analogue of the FIT. But it was not quite clear how ‘close’ is the analogy between the DFT of the form (1) and the classical FIT. The point is that the eigenfunctions fn (x) = Hn(x) exp(−x2∕2) of the FIT represent an important explicit example of an orthonormal and complete system in the Hilbert space  of square-integrable functions on the full real line

of square-integrable functions on the full real line  . It is further well known that the functions fn(x) exhibit some particular symmetry properties, which are direct consequences of the underlying symmetries of the number operator N that governs them. For instance, the functions fn(x) are either reflection symmetric or antisymmetric, that is,

. It is further well known that the functions fn(x) exhibit some particular symmetry properties, which are direct consequences of the underlying symmetries of the number operator N that governs them. For instance, the functions fn(x) are either reflection symmetric or antisymmetric, that is,  . Also, the functions fn(x) form a ladder-type hierarchy, in which the lowest function f0(x) is defined as an eigenfunction of the lowering operator, associated with the zero eigenvalue, and all higher eigenfunctions are successively defined by the action of the raising operator (cf. (8) and (9)). So, the question of defining how close are the DFTs to their continuous archetype FIT actually can be formulated as ‘how many symmetry properties of the FIT eigenfunctions fn (x) are shared by the eigenvectors of discrete Fourier transforms’.

. Also, the functions fn(x) form a ladder-type hierarchy, in which the lowest function f0(x) is defined as an eigenfunction of the lowering operator, associated with the zero eigenvalue, and all higher eigenfunctions are successively defined by the action of the raising operator (cf. (8) and (9)). So, the question of defining how close are the DFTs to their continuous archetype FIT actually can be formulated as ‘how many symmetry properties of the FIT eigenfunctions fn (x) are shared by the eigenvectors of discrete Fourier transforms’.

We have seen in Section 2 that the eigenvectors of the discrete number operator  based on points N do have symmetry properties in common with the eigenfunctions fn(x) of FIT only if the number of those points is odd. The case of even N’s turns out to be more complicated: although the discrete number operator

based on points N do have symmetry properties in common with the eigenfunctions fn(x) of FIT only if the number of those points is odd. The case of even N’s turns out to be more complicated: although the discrete number operator  and the number operator N have similar symmetry properties for generic N, the set of the eigenvectors of the

and the number operator N have similar symmetry properties for generic N, the set of the eigenvectors of the  with even N has a different structure than its continuous counterpart. An important aspect to observe in this connection is that there is a close similarity of this case of even N’s with those quantum and classical systems, in which symmetries are (hidden) spontaneously broken, in spite of the fact that ‘spontaneous symmetry breaking (SSB) actually does not occur in the case of finite physical systems’ (see, for example, [11]). So, finite systems with SSB seem to show up in the discrete (finite) analogues of the quantum-mechanical harmonic oscillator.

with even N has a different structure than its continuous counterpart. An important aspect to observe in this connection is that there is a close similarity of this case of even N’s with those quantum and classical systems, in which symmetries are (hidden) spontaneously broken, in spite of the fact that ‘spontaneous symmetry breaking (SSB) actually does not occur in the case of finite physical systems’ (see, for example, [11]). So, finite systems with SSB seem to show up in the discrete (finite) analogues of the quantum-mechanical harmonic oscillator.

It may also be worth mentioning that due to SSB in the case of even dimensions N it is not possible touse the same procedure of constructing eigenvectors for the discrete number operator  in the form of the ladder-type hierarchy, defined by (8) and (9). Nevertheless, we have found a systematic way for explicitly constructing the eigenvectors of the discrete number operator

in the form of the ladder-type hierarchy, defined by (8) and (9). Nevertheless, we have found a systematic way for explicitly constructing the eigenvectors of the discrete number operator  for even N’s.

for even N’s.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Paul Terwilliger for illuminating discussions that assisted us, in particular, to find a simple way of deriving the cyclic form of the characteristic equation (21) for the raising and lowering difference operators. We thank Fernando González and Magdalena Hernández for their technical help with the figures. J.L.-H. is grateful to the Unidad Cuernavaca del Instituto de Matemáticas, UNAM, for the hospitality during his sabbatical stay there on August 01, 2017 – July 31,2018, supported by the CONACYT ‘Apoyo para Estancias Sabáticas Nacionales 2017(1)’, announcement 291160. The participation of NMA in this work has been supported by the project ‘Óptica Matemática’ IG100119, awarded by the Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

References

- Atakishiyeva MK, Atakishiyev NM (2015), On the raising and lowering difference operators for eigenvectors of the finite Fourier transform. J Phys: Conf Ser 597, 012012 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Atakishiyeva MK, Atakishiyev NM (2016), On algebraic properties of the discrete raising and lowering operators, associated with the N-dimensional discrete Fourier transform. Adv Dyn Syst Appl 11, 81–92 [Google Scholar]

- Sylvester JJ (1867), Thoughts on inverse orthogonal matrices, simultaneous sign successions, and tessellated pavements in two or more colours, with applications to Newton’s rule, ornamental tile-work, and the theory of numbers. Philos Mag 34, 461–475 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Koekoek R, Lesky PA, Swarttouw RF (2015), Hypergeometric orthogonal polynomials and their q-analogues, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg [Google Scholar]

- Landau LD, Lifshitz EM (1991), Quantum mechanics (non-relativistic theory), Pergamon Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- Atakishiyeva MK, Atakishiyev NM, Méndez Franco J (2016), On a discrete number operator associated with the 5D discrete Fourier transform, Differential and difference equations with applications, Vol. 164 of Springer Proceedings in Mathematics & Statistics, Springer, NY, pp. 273–292 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan JH, Parks TW (1972), Eigenvalue and eigenvector decomposition of the discrete Fourier transform, IEEE Trans Audio Electroacoust AU-20, 66–74 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Auslander L, Tolimieri R (1979), Is computing with the finite Fourier transform pure or applied mathematics ? Bull Am Math Soc 1, 847–897 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro H (2015), Linear algebra and matrices, AMS, Providence, Rhode Island [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DJS (2006), A course in linear algebra with applications, World Scientific, Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Brading K, Castellani E, Teh N (2017), Symmetry and symmetry breaking, in: EN Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Archive, Winter 2017 edn., Stanford, USA. [Google Scholar]

Cite this article as: Mesuma K. Atakishiyeva, Natig M. Atakishiyev and Juan Loreto-Hernández (2019), More on algebraic properties of the discrete Fourier transform raising and lowering operators. 4open, 2, 2.